Some jobs are tailor-made for those who enjoy a drink.

Being a chef is one. Working in entertainment is another. The newspaper business also fits nicely in to that group. I’ve worked in all three.

The first was as a chef at Butlin’s Holiday Camp.

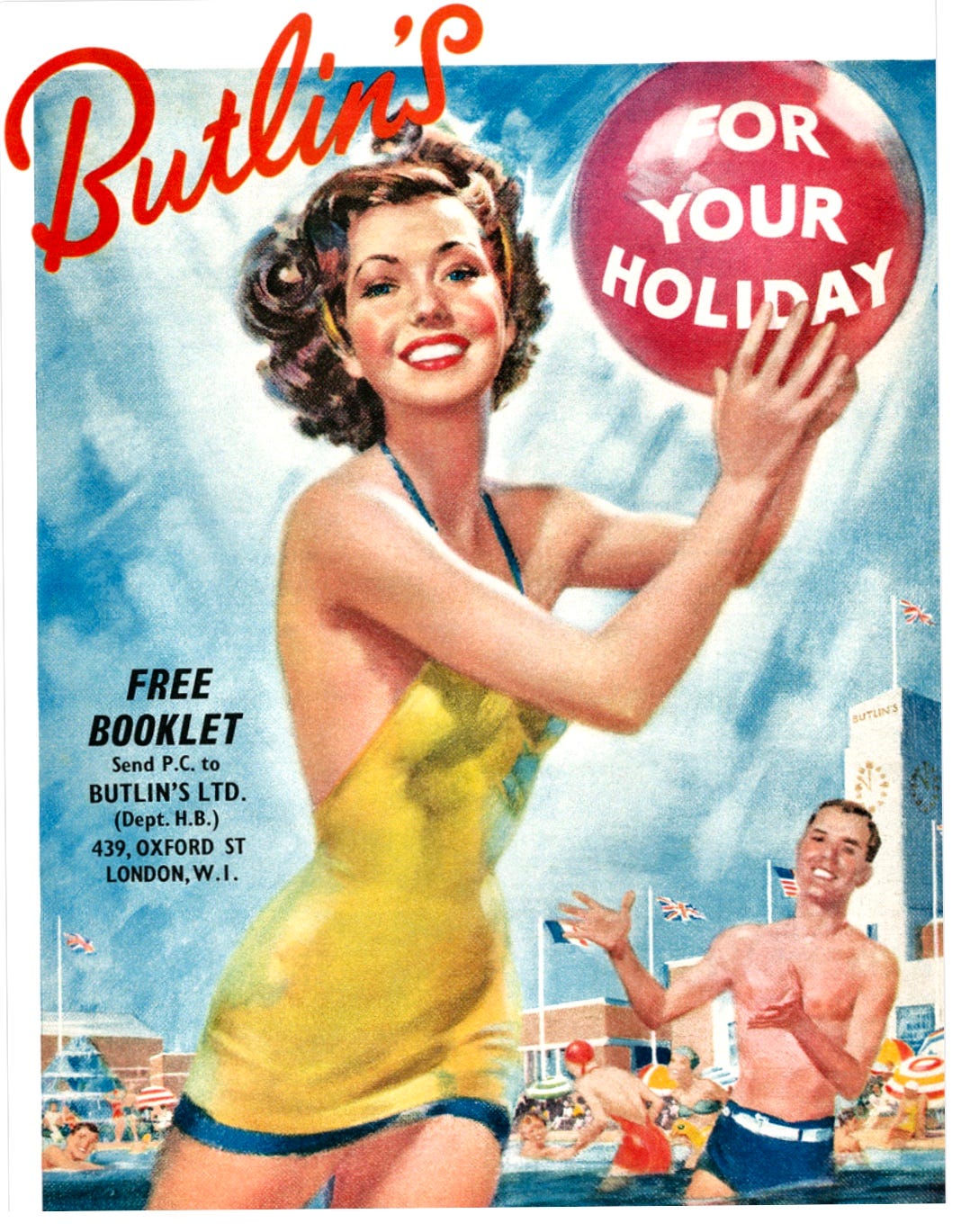

I expect most people outside the UK (Probably some inside the UK as well) are unfamiliar with the institution that once was Butlins.

Well, here goes...

Butlins was a chain of holiday camps where British families could escape their everyday lives, park their kids with an underpaid Redcoat, and get thoroughly pissed for a week…… What’s not to like?

I had worked as a grill chef in a few restaurants but found myself “between jobs,” as the unemployed like to say. My reduced circumstances meant I was drinking less—not by choice, but by necessity.

High unemployment meant I was required to make a twice-weekly pilgrimage to the “Job Centre” as a condition of receiving benefits. The centre had an air of desperation and boredom seldom experienced outside of a prison.

The process was as pointless as it was tedious—this was the end of the seventies and both sides knew there were no jobs.

A typical conversation with the bored clerk went something like this:

Clerk: “What sort of work are you looking for?”

Me: “Chimney sweep.”

Clerk: “Are you trying to be funny?”

Me: “Well, you started it.”

Once I’d confirmed my active job search status, I would scan the notice boards for non-existent opportunities. The good jobs never made it to the majority of jobseekers —they were plucked straight off the board by anyone quick enough to shove the card in their pocket, thus instantly reducing competition.

One day, in a rare twist of fate, I found one still there:

"Come and work at Butlin’s for the summer season, the card announced."

A mass hiring was underway for everything from bar staff to cooks. I pocketed the card, approached the desk, and asked, "What’s all this about Butlin’s?"

After an interview and months of waiting, my golden ticket arrived in mid-April:

Assistant Cook, start date in May.

I cannot truly express the relief I felt having something to look forward to.

Butlin’s holiday camps in the late 70s were the ultimate destination for British families looking to escape the drudgery of everyday life.

The camp I was assigned to, in Somerset, was the largest of nine across the country. It could accommodate twelve thousand guests. Add another two thousand staff, and it wasn’t so much a holiday camp as a small town, run with military-style efficiency.

Guests didn’t exactly camp; they stayed in rows of chalets and dined in vast halls humorously referred to as Restaurants. Needless to say, the term “Restaurant”might not hold up in a court of law.

I didn't mind it wasn't fine dining, and the other 2,000 staff thought the same way.

We were all around the same age, thrilled to be getting paid to live at a holiday camp for six months. It promised fun, freedom, and of course, plenty of booze.

Butlin’s also happened to be in the heart of Somerset, the epicentre to the strongest natural cider known to man. A foul, throat-stripping liquid, best reserved for my days off.

During work hours, there were bigger fish to fry. Literally.

I was assigned to a dining hall, serving fifteen hundred people per sitting, three times a day. Across the camp, cooks prepared meals for thousands of campers, starting at dawn and working through the night. A team of us would be responsible for, say, frying hundreds of eggs or roasting six hundred chickens. It was food production on an industrial scale.

On one memorable occasion, I was assigned mashed potatoes.

Except these weren’t “mashed” in the traditional sense—they were instant.

At home, instant mash is simple: pour granules into a bowl, add hot water, stir, and voilà! A creamy delight for the whole family to enjoy.

At Butlin’s, things were a little different. First, you emptied a large sack of granules into a stainless-steel cement mixer. Then, you grabbed a hose, filled it with hot water, and switched the mixer on. Give it a minute or two later and voilà! enough mash to feed an army.

Except, on this particular occasion, I made a miscalculation.

I was made aware of my shortcomings when the catering manager burst into the kitchen and demanded, “Who made the mashed potatoes!”

A dozen fingers pointed at me.

"Come and look at this dickhead!" she snapped.

I followed her into the dining hall and was met with an extraordinary sight. Roughly a thousand people were struggling to swallow dry, under-hydrated instant mash.

The noise was something else—the collective effort of hundreds of diners trying to swallow the un-swallowable created a bizarre, rhythmic clip-clopping sound, like a stampede of horses trotting through wet mud.

Those who hadn’t taken the mash watched in confusion, witnessing what can only be described as a truly bizarre spectacle.

After all, it’s not every day you see a thousand people with such collective concentration on their faces at the same time—mainly due to the sheer effort of trying not to choke.

Lesson learned: when making mashed potatoes in a cement mixer, always use enough water.

If this proved to be "Thirty work", at the end of the shift, no need to worry.

The camp had plenty of bars, including The Pig and Whistle, the longest bar in the UK. Employees had full access—not just to the public bars but also to a staff-only bar, which stayed open after hours.

After the staff bar had shut, it was off to each other's chalets, for some drinks, followed by a few hours of sleep before heading back to work. For six months, I was out almost every night with new friends, thoroughly enjoying myself.

What a comedown it was when the season ended in September, just as I was settling into the routine.

During this time, I witnessed another side of life, different from the dreary, monotonous existence I was accustomed to—This was far better.

"I had discovered ‘The Thirst’ for a good time, all the time."